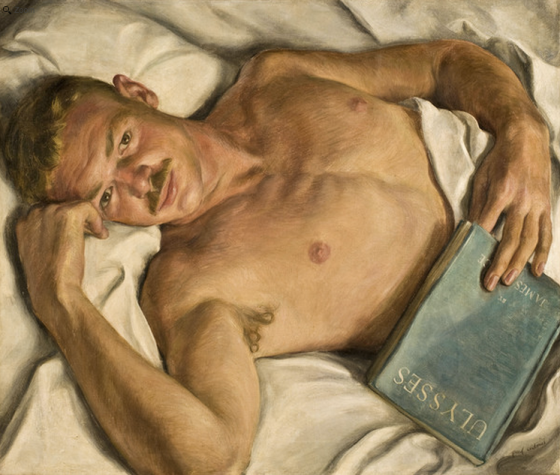

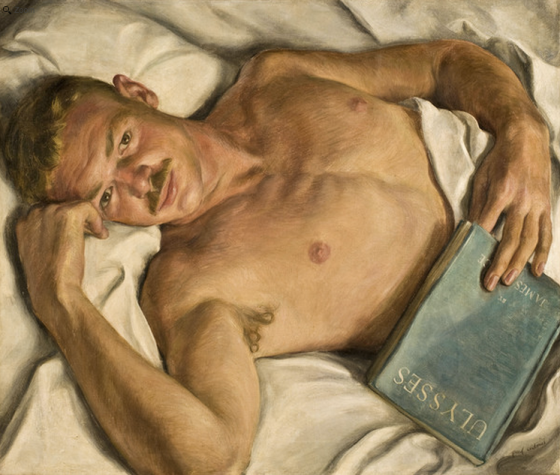

A few days late, but I wanted to acknowledge Jared French’s birth date on February 4 by posting a few thoughts on Jerry, Paul Cadmus’s 1931 portrait of French. The painting so immediately conveys that the two artists were lovers–a complex relationship the men maintained even after French’s marriage to Margaret Hoening, a fellow artist which they together artistically collaborated with under the clever acronym PaJaMa –that it is one of the reasons, I imagine, that it was not publicly seen until the 1970’s and only recently transitioned from the French family’s personal collection to permanent display in a public institution (more detailed information via Tyler Green).

A few days late, but I wanted to acknowledge Jared French’s birth date on February 4 by posting a few thoughts on Jerry, Paul Cadmus’s 1931 portrait of French. The painting so immediately conveys that the two artists were lovers–a complex relationship the men maintained even after French’s marriage to Margaret Hoening, a fellow artist which they together artistically collaborated with under the clever acronym PaJaMa –that it is one of the reasons, I imagine, that it was not publicly seen until the 1970’s and only recently transitioned from the French family’s personal collection to permanent display in a public institution (more detailed information via Tyler Green).

Jared French, August 1938 by George Platt Lynes

The intimacy of the portrait is striking, in terms of not only location (a rumpled, obviously slept-in bed) and proximity (even photographs don’t often dare creep so close to its human subject), but also in terms of its gaze: that of the artist behind the easel, of course, but also the one frankly and uninhibitedly returned by the subject himself. Usually when a subject gazes directly out of the image–be it a painting, photograph, film, or anything else–it is characterized as engaging the viewer and/or audience, but whenever I look at this image I’m struck that the facial expression and eye contact Cadmus captures makes me feel as if I’m not being implicated at all, but merely allowed to witness an intimate exchange that I’m not necessarily being invited to participate in. Somehow the image maintains its secrets and privacy despite its ostensibly exhibitionist display.

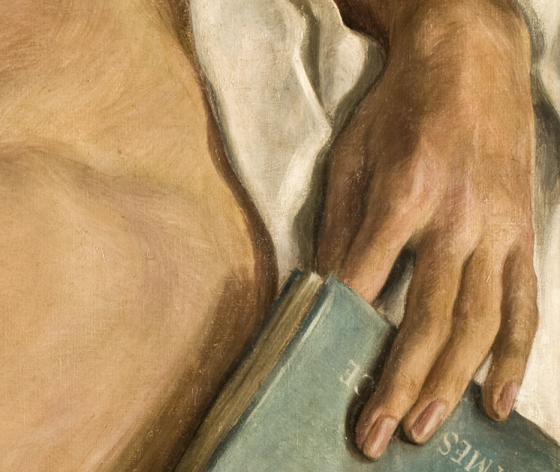

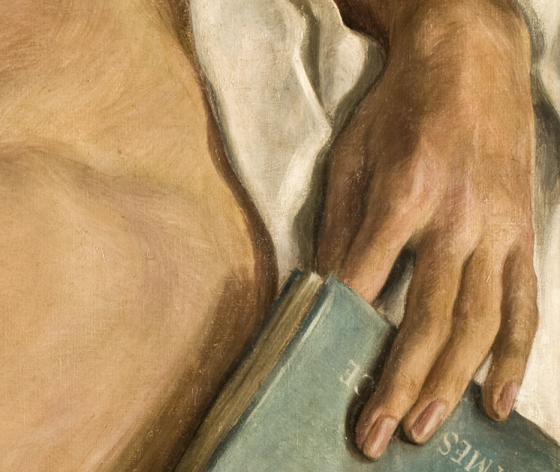

It’s also impossible not to be intrigued by the conspicuous presence of James Joyce’s Ulysses, which as John Coulthart notes, was a text banned in America at the time, and would be for several more years (he even wonders if it’s the first painted representation of the novel). But following the project Russell Meyer undertakes in his study of Cadmus’s work in Outlaw Representation: Censorship & Homosexuality in Twentieth Century Art, I am drawn to the idea that Cadmus employs the presence of one obvious illicit element (Ulysses) to signify another (the love “that dare not speak its name”). It’s a delightful visual strategy.

I generally have mixed feelings in regards to much of Cadmus’s work, conceptually appreciating what he is doing but not responding to his intentionally swollen and vulgar aesthetic, but Jerry has become one of my very favorite pieces of art not only of the modernist era, but just in general. It’s a marvelous testament to a relationship, be it erotic, artistic, and/or otherwise.

The 1000 Museums website has an amazing high resolution image of Jerry that allows for the painting to be inspected in closer detail than I’ve ever had the opportunity to do so before (and is probably the next best thing to seeing it in person at the Toledo Museum of Art). In line with Jerry‘s celebration of intimacy, here are a few details from the painting to scrutinize–and savor.

Provenance

Jerry (1931)

Paul Cadmus

Oil on canvas

Toledo Museum of Art

Jared French, August 1938

George Platt Lynes

Gelatin silver print

Metropolitan Museum of Art