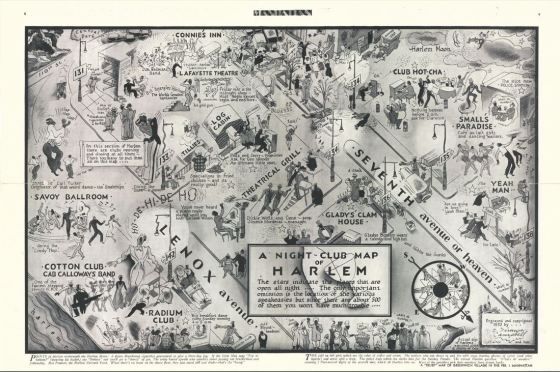

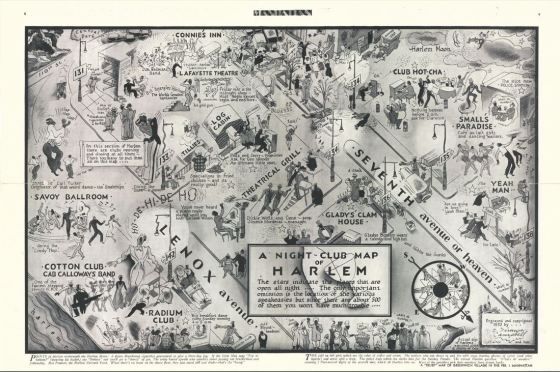

In my internet searching I’ve come across this vivid cartoon map of Harlem several times now, but until today I hadn’t really taken the time to look at what is actually depicted. Frank Jacobs gives a terrific and detailed overview of the map here, and explains that it is the work of Elmer Simms Campbell (1906-1971), “the first African-American cartoonist to be published nationally.” In the bottom right corner it is listed as being “engraved and copyrighted in 1932.”

What I was most curious about was whether or not the map gave any indications of a queer presence in the Harlem of the early 1930’s. The historical importance of Harlem to the queer community is well known; as George Chauncey notes in the ever-essential Gay New York, while Greenwich Village “was considered the city’s most infamous gay neighborhood by outsiders” in the 20’s and 30’s, “many gay men themselves regarded Harlem as the most exciting center of gay life” (227). So is this indicated at all in Campbell’s map?

Daniel Crouch Rare Books has a nice high-quality scan of the map which allows for close(r) inspection. As far as my eyes can tell, nothing queer is obviously conveyed, none of the people or places depicted signal queerness of any kind: the patrons are all heterosexually paired, none of the performers or proprietors—except for one major and well-known exception, described below—don clothing or assume gestures that could be considered suspect. A pairing of two men up in the top left corner might be construed as a covert cruising encounter, but the attributed dialogue (“what’s da numbah?”) is revealed in the description at the bottom as a common reference to gambling. In short, Campbell’s representation of Harlem doesn’t seem to offer up any queer secrets.

However, “a handful of clubs catered to lesbians and gay men,” Chauncey writes, “including the Hobby Horse, Tillie’s Kitchen, and the Dishpan, and other well-known clubs, including Small’s Paradise, welcomed their presence” (252). Two of these, Tillie’s Kitchen and Small’s Paradise, are accounted for by Campbell:

Which brings us, finally, to the map’s single overtly queer presence, located literally at the center of Campbell’s map: Gladys Bentley at the piano at the Clam House. Bentley is a fascinating pioneering figure I can’t do justice to here (The Root provides a nice appreciation here though), but, to return once again to Chauncey, Bentley is characterized as “the most visible lesbian” in Harlem at that time, “as famous for her tuxedo, top hat, and girlfriends as for her singing” (252). Here’s how Campbell depicts the notorious entertainer—an imposing and androgynous figure at the piano—alongside a now-iconic photo of her:

According to Chauncey, the Clam House “attracted an interracial audience of literati and entertainers, including many gay and lesbians;” Carl Van Vechten based a character on Bentley in one of his novels. She certainly deserves her own post at some point here at Queer Modernisms, but to close I can’t resist quoting one of her famously ad-libbed songs which she generously adorned with “filthy lyrics” and then “encourag[ed] her audience to join in singing.” As Chauncey records it, Bentley transformed the standard “Sweet Georgia Brown” into “Alice Blue Gown,” an “ode to anal intercourse:”

And he said ‘Dearie, please turn around!’

And he shoved that big thing up my brown.

He tore it. I bored it. Lord, how I adored it.

My sweet little Alice Blue Gown. (252).

My, my: sounds like a gay ol’ time indeed!

Works Cited:

Chauncey, George. Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Makings of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940. New York: Basic, 1994. Print.