[To continue celebrating Djuna Barnes this week and because I was thinking about it in light of a film adaptation currently in the works, I’ve decided to revisit and expand this review which was originally posted on Goodreads.]

…

“‘The Night-Life of Love,’ said Saint Musset, ‘burns I think me in the slightly muted Crevices of all Women who have been a little sprung with continual playing of the Spring Song, though I may be mistaken, for be it known, I have not yet made certain on this point.'”

Even after more than eight decades critics and scholars still squabble over what exactly Djuna Barnes was trying to accomplish with her Ladies Almanack. Is it an affectionate satire? An exuberant celebration? A sly denunciation? A parodic exercise in self-loathing?

Of course, this is Djuna Barnes we are talking about, so it’s probably all of these things, though perhaps “none of the above” gets even a bit closer to the heart of the matter. But these tensions touch upon exactly the thing that most compels me most about Barnes’s text—it somehow can manage to encompass nearly all interpretations one could possible pose, but stakes itself definitively to none of them. Which makes it a superlative example of one of my academic interests: the conveyance of queer content through “queered” form.

Photograph of Djuna Barnes and Natalie Clifford Barney, c. 1930.

The Almanack is deliberately constructed to work simultaneously on two different levels, with different sets of meaning available to different communities of readers. For the uninitiated the text can come off as a rather bewildering–perhaps even incomprehensible–take on medieval hagiography, with its mock-reverent depiction of Dame Evangeline Musset and her seemingly limitless benevolence toward young women in need.

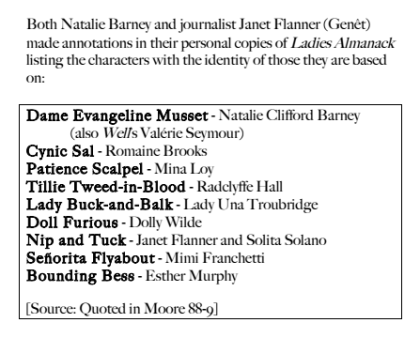

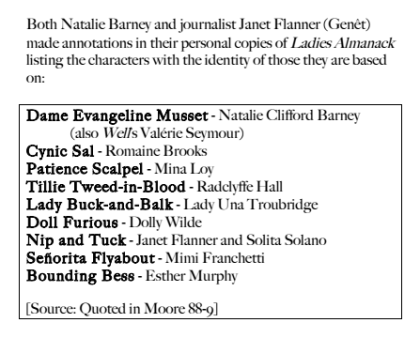

Some readers, however, might also pick up that Dame Musset’s munificence is not purely altruistic in nature, but extends to a more sensual dimension that involves the women’s “Hinder Parts, and their Fore Parts, and in whatsoever Parts did suffer them most” (Barnes 6). But Barnes herself readily admitted that her Almanack was more than anything intended for “the private domaine” [sic], to be “distributed to a very special audience” (cited Lanser 164); that “special audience” was first and foremost Natalie Clifford Barney, as well as the many members of the lesbian-centric coterie that assembled around her in Paris. And not only was Barney & co. the audience that would be able to understand the layers of meaning shrouded within the narrative, they comprised of the subject matter themselves, as the text’s expansive cast of characters all had real-life counterparts that were being wittily caricatured (see below).

Key to the characters of Ladies Almanack I once made for a seminar presentation.

Privately printed and distributed, it’s interesting to consider how the Ladies Almanack was part of a spontaneous(?) flowering of literature published in 1928 that prominently featured same-sex desire–and sometimes dared even more–between women, including Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, Compton Mackenzie’s Extraordinary Women, The Hotel by Elizabeth Bowen, and, perhaps most importantly in a purely historical sense, Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness (for a good consideration of the importance of the year 1928 to feminist and/or lesbian texts I highly recommend Bonnie Kime Scott’s important 1995 study Refiguring Modernism, Volume I: The Women of 1928).

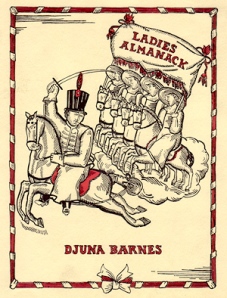

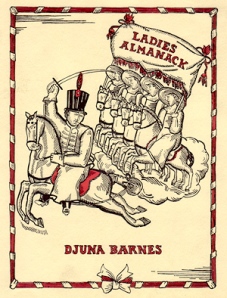

Original illustration by Djuna Barnes for Ladies Almanack

It is particularly enlightening to contrast Ladies Almanack to the latter of these novels, for not only does Hall, along with her longtime partner Una, Lady Troubridge, make appearances within Barnes’s text, but it throws into sharp relief Barnes’s own aim and approach in regards to both content and aesthetics. On the most obvious level, Barnes’s obscure, archaic utilization of language and form in the Almanack is a far cry from Hall’s unambiguously presented apologia-cum-petition. But unlike the wealthy Hall who could use her artistocratic lineage and social privilege to withstand public backlash, Susan Snaider Lanser writes that for Barnes, penniless and an American expatriate, it was “better to shroud [the overtly lesbian content] in obscurity, generating a prose whose meanings dissolve beneath a torrent of difficult words and sentences” (166).

As such, Ladies Almanack can’t just be considered an example of willful high modernist obfuscation; at the same time, its stylistic choices can’t just be solely marked up as a method for eluding censorship either. Rather, it’s something between, I’d argue, an alchemical concoction that attempts to avoid simply shoehorning queer–and intensely personal and private–topics and desires into traditional novelistic forms (The Well of Loneliness again, which can make for a rough reading experience today in its relentless proselytizing), with the purpose of beginning to articulate a new means of expression altogether. Barnes accomplishes this by queerly cherry-picking elements from a variety of sources both historical and modernist, which makes it a kind of anomaly, much like her much more well-known Nightwood, within high modernist literature, of which she was one of the most prominent (if perpetually undervalued) figures.

All these factors–and many others I’m necessarily sidestepping at present–lead to a text that is at once both outdated and undateable, and as playfully and deliberately enigmatic today as it must have been in 1928.

And hell, it’s just an awful lot of fun.

Djuna Barnes’s original illustration of Dame Musset’s funeral. Let’s just say it’s this is not the bleak scene you might assume it is…

WORKS CITED

Barnes, Djuna. Ladies Almanack. (1928). Elmwood Park, IL: Dalkey Archive, 1992. Print.

Lanser, Susan Sniader. “Speaking in Tongues: Ladies Almanack and the Discourse of Desire.” Silence and Power: A Reevaluation of Djuna Barnes. Ed. Mary Lynn Broe. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 1991. 156-68. Print.

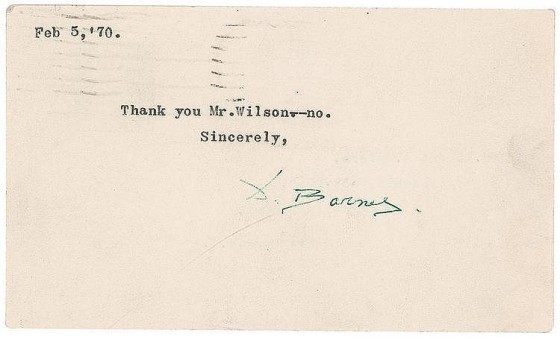

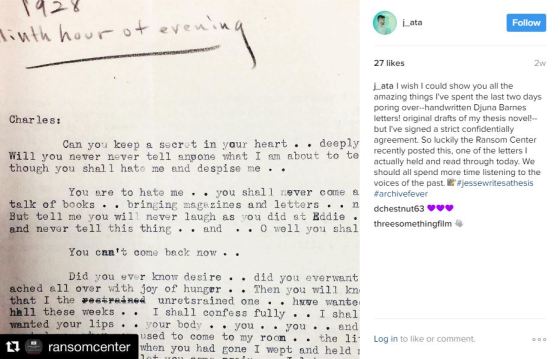

The most important development which specifically warrants an update post, however, is that after many years of hoping and scheming I was finally able to do some actual archival research for this thesis. Two weeks ago I spent three days at the University of Austin’s

The most important development which specifically warrants an update post, however, is that after many years of hoping and scheming I was finally able to do some actual archival research for this thesis. Two weeks ago I spent three days at the University of Austin’s

By the time I felt like I was finally getting a handle on this bitter, black-hearted little novel, it was all over. As I quickly discovered, to make the acquaintance of these titular two ladies is to be initiated into a state of perpetual disorientation; I was not, I’ll frankly admit, adequately prepared, even if Bowles’s novel frequently brought to mind the work of her contemporaries

By the time I felt like I was finally getting a handle on this bitter, black-hearted little novel, it was all over. As I quickly discovered, to make the acquaintance of these titular two ladies is to be initiated into a state of perpetual disorientation; I was not, I’ll frankly admit, adequately prepared, even if Bowles’s novel frequently brought to mind the work of her contemporaries