Here I find myself, perched upon the inaugural days of a brand new year that is as “fresh,” to quote one of the opening lines of Mrs. Dalloway, “as if issued to children on a beach.” Of course I’m inevitably forced to reckon with the unrealized intentions of what I intended Queer Modernisms to become over the course of 2014, almost none which ultimately came to pass. There are lots of reasons for this, most of which are exceedingly banal, but I’m relieved to report that current circumstances are undergoing a process of rapid change, and soon I’m going to have much more time–and, more importantly, the energy–to devote to this project which I still hold very dear and have many aspirations for.

The cycle of one year completing and another one beginning has always sparked in me the impulse to reflect and reevaluate. This quality is accentuated by the fact I derive an intense pleasure out of trying to discover and trace the patterns lurking unexpectedly within then past, and then attempting to make some kind of sense out of them. As such, for this first post of 2015 I intend to exactly that: go back and (re)consider my reading habits over the last year. In 2014 I watched less films than I probably ever have, but perhaps as a direct result I experienced what turned out to be an incredibly rich year in my reading, and I want to record–and celebrate–it.

I managed to write about and post several book reviews over the course of the year, but most others that I intended remain in draft form or simply as scribbled notes–if I even got that far in the process at all. I do have a list of books I still intend to go back at some point and give a a full consideration, but alas, I suspect for most the brief and rather scattershot musings presented below will have to suffice. But hey, it’s something, right?

…

The first book that I picked up after completing the last course for my English M.A. program was one that had been hovering near the top of my to-read list for a long while: Christopher Isherwood’s elegant autumnal autobiography Christopher and His Kind. If I had realized how much of it is devoted to clarifying references contained within The Berlin Stories and other earlier texts–almost all of which I have not yet read–I might have held off, but it turns out prior knowledge is not at all necessary to enjoy Isherwood’s book. Rather, I was constantly drawn to the formal quality of “rewriting”–of Isherwood very consciously revisiting events that had found their way into his autobiographical writing over the years, and his attempt to later set the record “straight” about them. Wonderfully enough, being set “straight” in this situation entails being forthright about queer dimensions that had had to be necessarily encoded, deleted, or obscured. It’s a wonderful account of a great 20th century queer life, and the many figures and events that intersected it. In addition, with the careful differentiation between “Christopher” and “I” Isherwood perfectly captures the sensation I often experience when revisiting my own memories: of feeling at once both connected to and severed from them, as if they were observed but not actually experienced firsthand, and that it is only through the process of writing them down–and rewriting them again and perhaps even again–that makes them feel most “real.”

The first book that I picked up after completing the last course for my English M.A. program was one that had been hovering near the top of my to-read list for a long while: Christopher Isherwood’s elegant autumnal autobiography Christopher and His Kind. If I had realized how much of it is devoted to clarifying references contained within The Berlin Stories and other earlier texts–almost all of which I have not yet read–I might have held off, but it turns out prior knowledge is not at all necessary to enjoy Isherwood’s book. Rather, I was constantly drawn to the formal quality of “rewriting”–of Isherwood very consciously revisiting events that had found their way into his autobiographical writing over the years, and his attempt to later set the record “straight” about them. Wonderfully enough, being set “straight” in this situation entails being forthright about queer dimensions that had had to be necessarily encoded, deleted, or obscured. It’s a wonderful account of a great 20th century queer life, and the many figures and events that intersected it. In addition, with the careful differentiation between “Christopher” and “I” Isherwood perfectly captures the sensation I often experience when revisiting my own memories: of feeling at once both connected to and severed from them, as if they were observed but not actually experienced firsthand, and that it is only through the process of writing them down–and rewriting them again and perhaps even again–that makes them feel most “real.”

In addition, several books I read this last year emphasized once again how arbitrary it often seems that some texts, figures, and cultural artifacts manage to find a place within the historical consciousness while for some reason others simply do not. There actually exists an American novel from the Depression Era that not only openly represents gay desires and several criss-crossing male/male relationships, but actually allows space for a happy resolution? I didn’t really believe it either, and then I read Richard Meeker’s Better Angel. And yes, I can attest that such a novel indeed exists, and actually it’s a quite fine one at that. Not a literary masterpiece mind you, but an intelligently and sensitively written account of what is undoubtedly a story experienced by many men in the pre-Stonewall era. It has a stately beauty and wisdom in its plainspoken, often plaintive honesty that becomes particularly pronounced when compared to the hysterical tone taken by most contemporaneous texts that deal with similar subject matter. Meeker’s novel was one of the few books I did actually manage to do justice to and write a full analysis of, so I will direct all interested parties in that direction. It really is a really wonderful book, and unequivocally deserves a much more prominent spot within accounts of queer literature than it has been accorded to date.

Another novel in desperate need of further exploration and consideration both by myself and others is the singular Diana: A Strange Autobiography by Diana Frederics (a pseudonym, but that’s a whole separate, utterly fascinating story in and of itself!). Published in 1939 by the Citadel Press, just a glance through the chapter names listed in the table of contents announces its disarmingly forthright approach towards its so-called “strange” content: “Am I A Lesbian?,” “‘I Am A Lesbian!’,” “Leslie and I Become Lovers,” etc. Throughout The Well of Loneliness Radcylfe Hall cloaks her representation of lesbian desires and lives with elaborate–and ultimately deadening–metaphors and other explicit literary devices, and Diana opts for the opposite tack. Consider:

Another novel in desperate need of further exploration and consideration both by myself and others is the singular Diana: A Strange Autobiography by Diana Frederics (a pseudonym, but that’s a whole separate, utterly fascinating story in and of itself!). Published in 1939 by the Citadel Press, just a glance through the chapter names listed in the table of contents announces its disarmingly forthright approach towards its so-called “strange” content: “Am I A Lesbian?,” “‘I Am A Lesbian!’,” “Leslie and I Become Lovers,” etc. Throughout The Well of Loneliness Radcylfe Hall cloaks her representation of lesbian desires and lives with elaborate–and ultimately deadening–metaphors and other explicit literary devices, and Diana opts for the opposite tack. Consider:

“With this acknowledgment of my homosexuality I discovered myself; now I had something to go on. It was like being born all over again, and the relief I felt astonished me. I had, so to speak, nothing left to be worried about. My fear were all confirmed… I was determined to respect myself for what I was, lesbianism be damned.”

Well yes, that final pronouncement doesn’t exactly jibe easily with our contemporary rhetoric of relentless pro-queer self affirmation, but I will attest that after reading so many books from this period–and let’s be frank, from all eras–where this same realization is accompanied by utter despair, followed by a quick and inevitably sad downward spiral, that the clear-eyed, no-nonsense attitude displayed by Diana’s eponymous subject had a lightening effect on me. With a rather spare, declarative style, it doesn’t take that long for Diana to pragmatically grasp evaluate the facts of her life and fearlessly set forth to make the best of things. And while there are inevitable complications along the way, she does manage to do pretty darn well for herself, and the fact that the concluding chapter of the novel is titled “Fulfillment” says quite lot. If this perspective came as a bit of a happy shock for me in 2014, I can only imagine its effect on a similarly sympathetic reader in 1939. That said, the few scholarly considerations I’ve been able to track down regarding Diana, most particularly Julie Abraham’s introduction to a 1995 reprinting by the NYU Press, take a surprisingly critical stance toward the novel, tending to focus on what the novel is not as opposed to the many things it is. One of my goals for this next year is to pen a few posts that begin to rectify this situation, as Diana was surely one of the great revelations of my reading year.

Stylistically, chronologically, and basically in all ways quite different from Diana but still quite wonderful exercise toward queer affirmation was Richard Amory’s groundbreaking erotic novel Song of the Loon. While at first glance it seems to be little more than an overripe sexual picaresque, very quickly the physical journey that structures the narrative begins taking on deep psychospiritual resonances as each handsome and hunky man the main character encounters helps him understand and embrace some part of his physical attraction to other men. The intentionally grandiose tone and mythic aspirations can seem rather overwrought and more than a bit silly when read today; perhaps even more difficult to tolerate is the representation of Native American culture and individuals, which is the stuff of “noble savage” archetypes. But by situating the world of Song of the Loon beyond any recognizable historical reality, it opens up a space of fantasy and electrifying possibility superseding the bounds of what in a historical sense would have been considered socially acceptable or approbatory in regards to depictions of male/male sexuality. It makes complete sense that Amory’s book became such a touchstone for an entire generations of gay men. To be quite honest, I kind of regret that my own generation hasn’t really been capable of retaining a space for this type of thing within our own (tenuously maintained) queer culture.

I finally took The Collected Poems of Frank O’Hara with the collage cover by Larry Rivers I’ve admired for so long off of the shelf and placed it instead on my nightstand. Picked up and perused over a period of several months during the summer, I found the poems themselves, so famously impressionistic in their itemized and/or offhand casualness and intimacy, to be perfectly suited for reading during “off moments:” say, in the minutes before drifting off to sleep, or as a way to delay for a few more minutes getting out of bed during weekends. As a naturally early riser I found myself returning constantly to the lovely “Getting Up Ahead of Someone (Sun),” and the concluding line “each day’s light has more significance these days” resonated with more than perhaps any other single line of writing I encountered this last year. I wouldn’t say that I’ve read this collection; rather, it remains is an entity I actively live and interact with, and I love that quality about it.

In one specific way Carson McCullers’s The Member of the Wedding was the most explicitly “queer” book I read this last year. The term itself constantly, even obsessively reappears through McCullers’s short novel, slowly building into a kind of incantation that transforms material that could be potentially dull and unnoteworthy into something rich and vivid and almost oversaturated with potential meaning. In McCullers’s capable hands the nondescript rural Southern town in which the novel is set is revealed to be an almost unbearably evocative psychological landscape pulsating with an intense emotional charge. McCullers absolutely deserves her reputation as one of the great prose stylists of 20th century American literature, and with The Member of the Wedding she crafted a perhaps the great depiction of the archetypal queer childhood.

Mishima has long been one of the major blind spots in my ongoing exploration of queer lit, something rectified this year with my reading of Confessions of a Mask. Alas, I was left surprisingly… indifferent by the experience. I fully admit that I often struggle with texts where suicide and other kinds of violence–towards the self or otherwise–are afforded prominent thematic positions (something I also experienced with my reread this year of another novel by a queer(ish) author, Flannery O’Connor’s Wise Blood), and I suspect this general disinclination was compounded by some fundamental problems with Meredith Weatherby’s lumpy translation, which also seemed to keep me forever at a distance. However, there was one great passage in the book that I still vividly remember read it one morning on the MUNI on my way to work: in two relatively short paragraphs Mishima managed to concisely explain how it is possible to have and maintain a split consciousness in regards to one’s sexuality, at once aware that the body is responding in a certain way and yet at the same time “never even dream[ing] that such desires… might have a significant connection with the realities of [his] ‘life.'” This one passage alone was enough for me to intuit that I should not write Mishima off completely, and so at the present I have filed both the author and his text under the category of “to return to someday.”

Mishima has long been one of the major blind spots in my ongoing exploration of queer lit, something rectified this year with my reading of Confessions of a Mask. Alas, I was left surprisingly… indifferent by the experience. I fully admit that I often struggle with texts where suicide and other kinds of violence–towards the self or otherwise–are afforded prominent thematic positions (something I also experienced with my reread this year of another novel by a queer(ish) author, Flannery O’Connor’s Wise Blood), and I suspect this general disinclination was compounded by some fundamental problems with Meredith Weatherby’s lumpy translation, which also seemed to keep me forever at a distance. However, there was one great passage in the book that I still vividly remember read it one morning on the MUNI on my way to work: in two relatively short paragraphs Mishima managed to concisely explain how it is possible to have and maintain a split consciousness in regards to one’s sexuality, at once aware that the body is responding in a certain way and yet at the same time “never even dream[ing] that such desires… might have a significant connection with the realities of [his] ‘life.'” This one passage alone was enough for me to intuit that I should not write Mishima off completely, and so at the present I have filed both the author and his text under the category of “to return to someday.”

Similar things can be said to characterize my feelings toward Andrew Holleran’s The Beauty of Men, one of my few forays into contemporary(ish) gay fiction this year. Selected by my boyfriend after an argument where he accused me of never reading the books he recommends to me, I was disappointed that the entire reading experience made me feel like a passive witness, recognizing the undeniable literary brilliance, but only feeling it at a distant, cold remove. This was particularly disappointing considering this is one of his very favorite books. Rather than empathizing with the overwhelming despondency over the way the AIDs crisis, geographical isolation, personal circumstances, and unreciprocated desire has left the main character’s life in a state of utter ruin, I was surprised to find myself more wrapped up in–and ultimately moved by–the gut-wrenching sadness hovering over his mother’s debilitating health condition(s). I still find it a bit mystifying that I generally seem more capable of relating to the queer literary output of the pre-Stonewall era than the literature that blossomed under the advancement of the Gay Rights Movement, and while acknowledging its great accomplishment, literary skill and observational acuity, The Beauty of Men ultimately reaffirmed this situation yet again.

On the other hand, one of the great literary pleasures of 2014 was Jewelle Gomez’s justifiably influential Gilda Stories. As I enthusiastically told friends how much I was reading and immensely enjoying this cycle of lesbian vampire stories, I would get vaguely patronizing smiles in response–I guess anything vampire-related gets that reaction these days–forcing me to trumpet all the more Gomez’s dazzling ability to intricately braid together the stuff of history, race, desire, time, and (im)mortality into a series of narratives that are not only compulsively entertaining to read, but poignant and thought provoking as well. While there was admittedly a slight sense of diminishing returns as Gilda’s life narrative progressed over its 200+ year trajectory, the central character of Gilda herself–fundamentally invariable as the distinctive contexts around her change like so many grade school dioramas–remains ceaselessly riveting.

On the other hand, one of the great literary pleasures of 2014 was Jewelle Gomez’s justifiably influential Gilda Stories. As I enthusiastically told friends how much I was reading and immensely enjoying this cycle of lesbian vampire stories, I would get vaguely patronizing smiles in response–I guess anything vampire-related gets that reaction these days–forcing me to trumpet all the more Gomez’s dazzling ability to intricately braid together the stuff of history, race, desire, time, and (im)mortality into a series of narratives that are not only compulsively entertaining to read, but poignant and thought provoking as well. While there was admittedly a slight sense of diminishing returns as Gilda’s life narrative progressed over its 200+ year trajectory, the central character of Gilda herself–fundamentally invariable as the distinctive contexts around her change like so many grade school dioramas–remains ceaselessly riveting.

It’s not uncommon for Sarah Orne Jewett’s The Country of Pointed Firs to be categorized as a lesbian (or more precisely, proto-lesbian) text: I’d personally say that judging strictly from what’s depicted within the narrative itself, such a characterization is more than a bit of a stretch. Instead, Country is an exquisite depiction of female homosociality in nineteenth century rural New England, its evocative vignettes masterfully capturing the interplay of nature and community in a society that has long since ceased to be. Along similar lines was W. Somerset Maugham’s The Razor’s Edge, which isn’t explicitly queer in any way, but which is easy enough to read as queerly coded text if one is so inclined: interpretations can surely be made regarding Larry Darnell’s resolute eschewal of the heteronormative life he seemed destined for, and it’s not particularly difficult to understand what Eliott Templeton’s hyper-stylized Continental prissiness is really supposed to signify. I actually ended up not caring much for the novel itself overall–I sensed it would have resonated with me about ten years ago, but that moment has long since passed–but I was continually drawn to Maugham’s tremendous empathy for his characters both as an author and as the first person narrator within the novel itself. I found myself endlessly intrigued that he ultimately seems to have little interest in distinguishing “negative” and “positive” qualities of his various characters, opting instead to present them as intricate constellations of characteristics through which to appreciate, empathize, and ultimately understand them. In the end it struck me as a wonderful exercise in empathy by the outside observer who is almost undoubtedly queer.

Of course it should come as no surprise that the queer always eludes demarcations and supersedes boundaries, with the propensity to appear unexpectedly. This was something I was reminded of constantly during my reading, and a particularly poignant example that haunted me for a long time after was a brief but unforeseen disclosure toward the end of J.L. Carr’s charming and quietly profound novella A Month in the Country, which emphasized yet again that queer lives, histories, and desires are often palimpsestically present within spaces–textual and otherwise–where they might otherwise not be expected.

Of the several book reviews I wrote this last year, one was for a book I very much liked and admired (John Preston’s Franny, the Queen of Provincetown), and one I enjoyed reading but was ultimately held some reservations toward (Edmund White’s Inside a Pearl: My Years in Paris).

Two books I enjoyed throughout the duration of 2014, and which I will continue reading into 2015: the respective journals of Glenway Wescott and of Hervé Guibert. As someone one who also avidly keeps a journals it is a literary form I particularly cherish. As such, I relished the time I spent perusing Continual Lessons: The Journals of Glenway Wescott, 1937 – 1955. Not only does Wescott capture his world–which is not only one that specifically fascinates me but which is of extreme relevance to this blog–with a charming and ultimately disarming blend of refinement and self-deprecating wit, I will fully admit that the daily struggles and insecurities recorded by this massively talented but temperamentally hesitant author was sometimes a source of solace for me as I too struggled with the restlessness and guilt of not accomplishing most of my own writing goals throughout last year.

Two books I enjoyed throughout the duration of 2014, and which I will continue reading into 2015: the respective journals of Glenway Wescott and of Hervé Guibert. As someone one who also avidly keeps a journals it is a literary form I particularly cherish. As such, I relished the time I spent perusing Continual Lessons: The Journals of Glenway Wescott, 1937 – 1955. Not only does Wescott capture his world–which is not only one that specifically fascinates me but which is of extreme relevance to this blog–with a charming and ultimately disarming blend of refinement and self-deprecating wit, I will fully admit that the daily struggles and insecurities recorded by this massively talented but temperamentally hesitant author was sometimes a source of solace for me as I too struggled with the restlessness and guilt of not accomplishing most of my own writing goals throughout last year.

On the other hand, for me time spent reading Hervé Guibert’s The Mausoleum of Lovers: Journals 1976 – 1991 often felt like temporarily wandering into an alien territory, affording me a glimpse into an interior landscape that I do not recognize in the least. Echoing my thoughts on Mishima, I often shrink from Guibert’s overt fascination with exploring and fantasizing over topics such as violence, cruelty, pain, death, and suicide, but every entry is crafted with razor-like incisiveness that always managed to keep me consistently riveted.

…

There are a few other texts I could write about, particularly theory and criticism, that I could record here, but I think this is as good a place as any to conclude.

And what am I reading at this moment? I’ve been enjoying wandering in and out of Melville’s incredibly strange, Pierre: or the Ambiguities in which I plan to read in conjunction with James Creech’s wonderful study Closet Writing/Gay Reading, and I began a collection of Wescott short stories just recently published for the first time, a thoughtful and much-appreciated gift from my partner for Christmas.

But there still remains so much to read, so now onward to 2015!

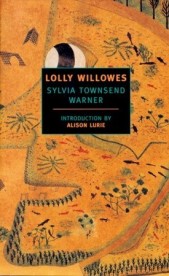

Warner’s prose sparkles and snaps like a gin and tonic in an elegant cut glass tumbler, her humor the slice of lime contributing the essential dash of sharp acidity. Warner proves to be a most devious hostess, however: seemingly invited to a pleasantly amusing afternoon garden party, it’s only as the sun begins to set that it suddenly begins to dawn—this is actually a Witch’s Sabbath! What a marvelously devious sleight of hand.

Warner’s prose sparkles and snaps like a gin and tonic in an elegant cut glass tumbler, her humor the slice of lime contributing the essential dash of sharp acidity. Warner proves to be a most devious hostess, however: seemingly invited to a pleasantly amusing afternoon garden party, it’s only as the sun begins to set that it suddenly begins to dawn—this is actually a Witch’s Sabbath! What a marvelously devious sleight of hand.

By the time I felt like I was finally getting a handle on this bitter, black-hearted little novel, it was all over. As I quickly discovered, to make the acquaintance of these titular two ladies is to be initiated into a state of perpetual disorientation; I was not, I’ll frankly admit, adequately prepared, even if Bowles’s novel frequently brought to mind the work of her contemporaries

By the time I felt like I was finally getting a handle on this bitter, black-hearted little novel, it was all over. As I quickly discovered, to make the acquaintance of these titular two ladies is to be initiated into a state of perpetual disorientation; I was not, I’ll frankly admit, adequately prepared, even if Bowles’s novel frequently brought to mind the work of her contemporaries