I was only several pages into Richard Meeker’s sensitive queer coming-of-age novel when it occurred to me that what I was reading was the flipside to Charles Henri Ford and Parker Tyler’s The Young and Evil, the novel I am currently in the process of writing my M.A. thesis on. Both novels were published in 1933 and both are often considered among the handful of texts that received publication in the first years of the 1930’s as the so-called “Pansy Craze” swept New York City and “book publishers race[d] to satisfy the public’s growing interest in the gay scene” (Chauncey 324).

I was only several pages into Richard Meeker’s sensitive queer coming-of-age novel when it occurred to me that what I was reading was the flipside to Charles Henri Ford and Parker Tyler’s The Young and Evil, the novel I am currently in the process of writing my M.A. thesis on. Both novels were published in 1933 and both are often considered among the handful of texts that received publication in the first years of the 1930’s as the so-called “Pansy Craze” swept New York City and “book publishers race[d] to satisfy the public’s growing interest in the gay scene” (Chauncey 324).

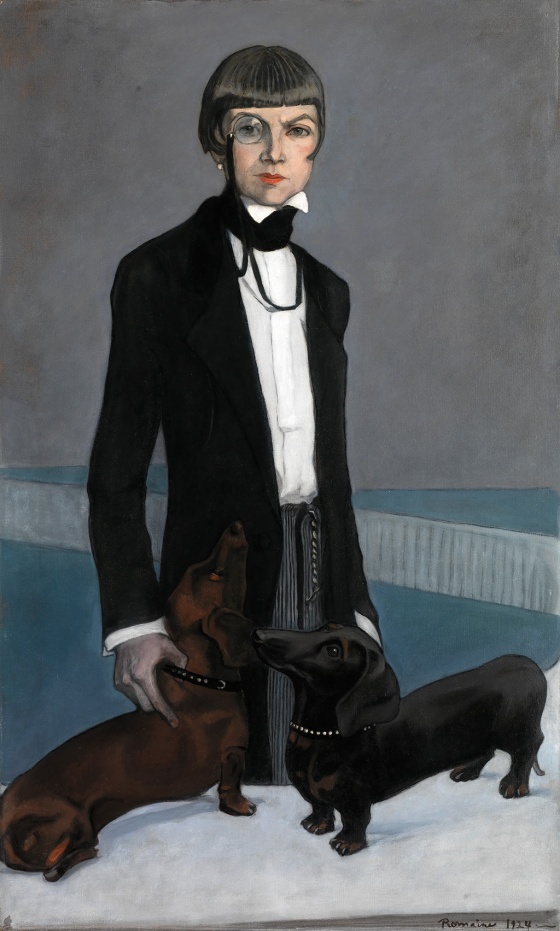

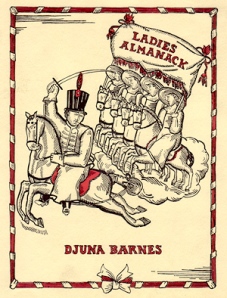

Despite a shared historical context, however, in many ways the two novels couldn’t be more different from each other. If the direct literary antecedents of Ford and Tyler’s exuberant, highly experimental depiction of the various sexual hijinks of several bohemian queers can be traced to the rather hermetic queer “high modernism” of Djuna Barnes and Gertrude Stein, then Better Angel, with its adherence to classical narrative conventions, forthright prose style, and candid appeal to a likely skeptical readership, is certainly within the tradition of Radclyffe Hall’s great queer populist classic The Well of Loneliness (1928).

Much like Hall’s novel, Better Angel reads like barely-concealed autobiography (something that it was eventually confirmed to be). The narrative begins when Kurt Gray is thirteen years old , an only child growing up in a rural small town. He is a shy, often lonely young boy, more inclined toward reading, music, and daydreaming than sports or the other activities the preoccupy his male peers. His is inevitably ostracized for this difference, which is a source of great anxiety and emotional trauma:

“…at last, hesitantly, perhaps in a flood of tears, he would admit that the boys at school had teased him about his fair skin: ‘Where’d ya buy yer paint, sissy? Sissy! Sissy!’–when, with a body shaking and hands clenched, eyes strangely dark in his white face, he would sob, ‘Why–Mom–why, why, why? Why can’t they leave me alone?’” (8)

Sadly, Kurt’s harrowing experiences don’t read today like a quaint situation from of a now long-distant past; instead, they will likely resonate deeply with many contemporary queer readers in regards to memories of merciless schoolyard bullying (it certainly did for this one). At his indignant mother’s suggestion, Kurt slowly begins to believe that his differences should not be regarded as a mark of shame but as a sign of his intellectual superiority–and as he ages the outer stoicism he has carefully developed begins to be perceived as scholarly excellence, and he begins to be regarded as an aspiring composer of great potential. His talent becomes his ticket for escaping his small town (first to university in New York) and eventually to Europe (on an academic scholarship), where he embarks on a journey of self-discovery, aided by a close friendship he develops with his classmate Chloe, his first tentative sexual experiences with her tempestuous brother Derry, and embarking on a relationship with the quietly intense David.

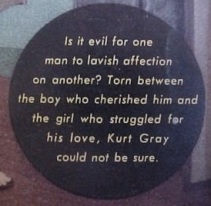

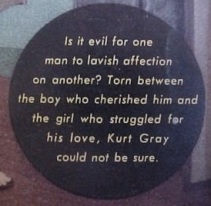

In the 1950’s the novel was reissued on paperback under the title “Torment”

What is particularly notable is how Kurt manages to accomplish this outside of the usual narrative tropes and historical trajectories common in queer stories of this era: he moves to New York City but deliberately avoids both the Village’s bohemian queer underworld and the queer enclaves embedded within the city’s vast theatrical and entertainment industries. Indeed, when the much more experienced David informs him of the social and sexual networks available to him, Kurt viscerally recoils, and instead throws himself into a world of aesthetic and egalitarian idealism, based on Platonic and other classical value systems (indeed, the Greek myth of Herekles and his favored youth Hylas plays a significant part in both the opening and conclusion of the narrative).

And, to his great credit, Kurt manages to succeed at his aims. Through the sheer force of his quiet self-will and self-control, he manages to construct a space for himself–and his personal happiness–outside of the more familiar currents of urban pre-Stonewall queer life. By the end of the novel, Kurt is dreaming of bucolic domestic living, renovating a rural farm for him and David to occupy while he teaches music at a progressive boy’s school in Connecticut.

“Torment” Cover Detail

Kurt’s personal idealism and self-restraint (which, admittedly, sometimes seems to border on the unnecessarily repressive), however, might turn out to be the source of his narrative preservation. Better Angel has been proposed as the first American queer-themed novel where the protagonist does not end in tragedy, whether it is enforced isolation, a rebuke their sexual orientation and past behavior, or even death; significantly, even in the 1950’s The Mattachine Society characterized Kurt as “perhaps the healthiest homosexual in print” (quoted Slide 128).

If earlier I drew parallels between Better Angel and The Well of Loneliness’s seemingly implicit intentions to be accessible to a general readership in terms of content, style, and tone, the great difference between the two texts is that contra Hall’s tendency to make Well a grand apologia, Angel rarely indicates any aspiration to be more than an earnestly told tale with the more modest intention, expressed in the epilogue appended many years later that it would reach “a good many of those who… would understand an appreciate it” (Forman 286).

Harry Burnett, Forman Brown, and Richard Brandon (l. to r.)

Like most of the “Pansy Craze” novels of the early 1930’s, Better Angel did not receive much attention in the press at the time of its initial publication, and it was reprinted in the 1950’s under the more dramatic but less appropriate title Torment (Slide 128). Happily, the author was later able to attest that from the beginning “the book did rather well, and to my delight, reached a good many of those who, as I hoped, would understand and appreciate it” (Brown 286). Richard Meeker, as it turns out, was the pseudonym for Forman Brown, who, along with Harry Burnett (who the character of Derry is based on) and Richard “Roddy” Brandon (David’s textual equivalent), established the Yale Puppeteers, a puppet theater group which become renowned for its collaborations with Elsa Lanchester (Slide 128-9). I plan to devote a future post to Brown and his rather remarkable reemergence and belated recognition as the author of Better Angel, but what is worth noting here is that the three men together formed a partnership–creatively and otherwise, from all indications–thus extending the narrative of Kurt, David, and Derry beyond the novel’s ambiguous concluding chapter.

According to Brown, many critics assumed that it was impossible for Kurt to enjoy a happy ending. However, the story his own life story, he insists, “demonstrate[s] how wrong a critic can be” (287). Such sentiments serve as a lovely–and unexpected–coda to this delicately rendered, still-underappreciated book.

…

Works Cited

Brown, Forman. “Epilogue (and Surprise Ending) for the New Edition.” Better Angel. 1933. Boston: Alyson Publications, 1987.

Chauncey, George. Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940. New York City: Basic, 1994.

The Mattachine Society. “Mission Statement and Membership Pledge (1951).” We Are Everywhere: A Historical Sourcebook of Gay and Lesbian Politics. Ed. Mark Blasius and Shane Phelan. New York: Routledge, 1997. 283-85.

Meeker, Richard. Better Angel. 1933. Boston: Alyson Publications, 1987.

Slide, Anthony. Lost Gay Novels: A Reference Guide to Fifty Works from the First Half of the Twentieth Century. New York: Harrington Park, 2003.