This blog is long overdue for an update—and a #jessewritesathesis update in particular. In brief: I’m chipping away at it! Progress doesn’t accumulate nearly as quickly as I’d like, of course, but I now have several docs that hold quite a bit of writing. Still learning to avert—or rather, manage—the crippling inner editor who insists that every sentence or phrase be “perfect” before moving to the next, but things are slowly improving.

The most important development which specifically warrants an update post, however, is that after many years of hoping and scheming I was finally able to do some actual archival research for this thesis. Two weeks ago I spent three days at the University of Austin’s Harry Ransom Center sifting through their extensive holdings on both Charles Henri Ford and Parker Tyler, and it just couldn’t have been a better experience. I was constantly impressed with how the Ransom Center and their staff were able to balance a (rightful) sense of protection over the remarkable material in their possession and an obvious commitment to access. As someone currently suspended somewhere between the categories of scholar and student, it was heartening to see that alongside the scholars were what seemed to be a constant stream of undergraduate students accessing and perusing material.

The most important development which specifically warrants an update post, however, is that after many years of hoping and scheming I was finally able to do some actual archival research for this thesis. Two weeks ago I spent three days at the University of Austin’s Harry Ransom Center sifting through their extensive holdings on both Charles Henri Ford and Parker Tyler, and it just couldn’t have been a better experience. I was constantly impressed with how the Ransom Center and their staff were able to balance a (rightful) sense of protection over the remarkable material in their possession and an obvious commitment to access. As someone currently suspended somewhere between the categories of scholar and student, it was heartening to see that alongside the scholars were what seemed to be a constant stream of undergraduate students accessing and perusing material.

[That said, even though the Center is extremely generous in allowing users to take as many photos of the material as they want, one must sign a strict confidentiality agreement that forbids sharing it without written permission. So unfortunately I can’t provide any images to accompany the things I mention below. Just an FYI—I’m not being stingy!]

What did I find? Well, that three days was hardly enough to even pretend that I’d managed to scratch the surface in regards to what’s available for discovery in both of these archives. It’s been very heartening to see both Ford and Tyler receiving increasing scholarly interest over the last year or so—something itself I should do a write-up one of these days—which leads me to assume that eyes are starting to get on this material (indeed, I was told someone had been working with the Ford material the week before I arrived), but it was also IMMEDIATELY clear that this is a “story”—indeed, multiple stories—that needs, is even demanding, to be told. Though I was forced to do a lot of scanning/speed-reading, Ford’s prolific correspondence (of which this is only a partial holding; there also seems to be much held at Yale’s Beinecke Library, to say nothing of holdings in archives of his countless correspondents) offers so much first-person documentation of modernism, American expatriatism, the pre-Stonewall queer experience, and early twentieth century American/European culture in general—in addition offering perspectives that have been generally kept to the peripheries of historical accounts of these eras and communities.

Image of a typical Djuna Barnes letter found online [NOT from the Ransom Center collection]

Other highlights: several draft fragments from The Young and Evil that provide insight into Ford and Tyler’s collaborative process, as well as facsimile copies of Ford’s correspondence with Gertrude Stein which helped illuminate her involvement with the text.

And finally, more information which only led to more mystery: one of the central enigmas that has emerged during my research is the figure of Kathleen Tankersley Young, a poet and critic initially associated with the Harlem Renaissance and appeared in a number of the “little magazines” of the period. As well as taking on a kind of mentorship role and co-editor credit for Ford’s literary magazine Blues, she is important to The Young and Evil, not only as the novel’s dedicatee but appearing as the text’s only major female character. From her poetry I had started to suspect that she is actually a more crucial influence on Ford and Tyler than even Barnes and Stein; reading through her letters has only confirmed this.

Yet despite all these fascinating connections (and others—she went on to found a minor but admired publication company before a tragic and mysterious early death) Young currently remains more or less invisible—indeed, the several mentions of her currently out there (mostly in studies and compilations of women connected to the Harlem Renaissance) can only mention that practically nothing is known about her. Indeed, I’ve yet to come across a photograph of her. I was cautiously hoping an image of some kind would emerge somewhere in Ford’s material, but that ended up not being the case (at least in what I was able to go through)—though I sense that a dramatic pencil sketch of a female face on one of her letters might be a portrait of her. I’m now more curious than ever about this fascinating, unknown figure; if anybody reading this happens to have ANY information on Young, please get in touch with me! (My info is in the “About” section.)

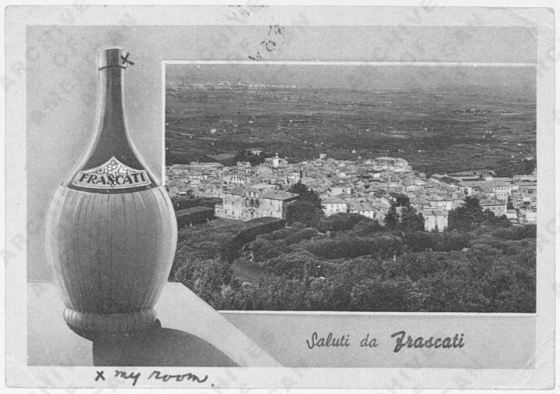

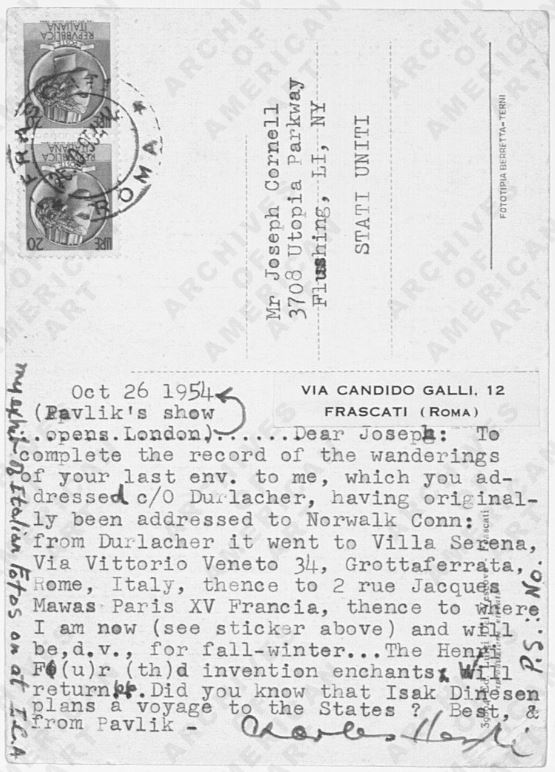

The Ransom Center actually shared on their Instagram account a snippet from one of letters from Young that I was able to look at, making it (I presume) ok to share here. I’ll also include below a few other images taken outside the restricted Reading Room.

It’s taken the two weeks since to simply organize and upload the notes and images (nearly 250 of them!) that I took over the course of the three days. Now it’s time to dive back into the writing—something I’m taking on again with a renewed sense of excitement and engagement. Wish me luck!

Top to bottom:

- Letter from Kathleen Tankersley Young to Charles Henri Ford (1928), posted on the Ransom Center Instagram account

- The eyes of Jean Cocteau from the interior of Ransom Center

- “Apparition” of Oscar Wilde on the exterior of the Ransom Center

- Original costume designed by Léon Bakst for Narcisse, performed by Diaghilev’s Ballet Russe (1911)