Sometimes a detail that appears in the frame of a film instantly seizes our attention and momentarily crowds everything else out–a situation I encountered during a recent rewatch of the 1958 film adaptation of Auntie Mame.

Sometimes a detail that appears in the frame of a film instantly seizes our attention and momentarily crowds everything else out–a situation I encountered during a recent rewatch of the 1958 film adaptation of Auntie Mame.

In the film’s second scene the young Patrick is introduced to his Aunt; she has misremembered her nephew’s date of arrival and he and his prim caretaker subsequently stumble into one of the lavish fêtes she regularly hosts at her extravagant Manhattan penthouse. Dumbstruck, the pair ogle the scene before them, and the film carefully showcases the wide range of eccentric individuals Auntie Mame associates with at the height of the hedonistic Roaring Twenties: a pianist playing ragtime while on his back, elderly Russian expatriates, raucous flappers, any number of “colorful” Asian and/or Middle Eastern figures in “traditional” garb–basically anyone conservative American audiences of the 1950s would likely find outré and/or politically suspect. As Mame careens through her rooms introducing her young nephew to anyone she encounters, she pauses momentarily to listen to the philosophical musings of one Acacius Page who is holding forth… to an indifferent room.

But honestly I’m a bit hazy about the whole interaction because I was immediately distracted by the two other figures literally perched on the edge of the widescreen Technicolor frame: two older women, clearly coded as bulldaggers. I was equally mesmerized by their unimpressed glaring–they contemptuously amused by Acacius’s demagoguing–as by their chic fedoras, tailored pinstripes, and wide masculine lapels.

Going back to take these screen captures, I also noticed that the pair exchange an eye roll and even a knowing wink when Acacius declares that the uniform at the children’s school he founded is to “wear nothing.”

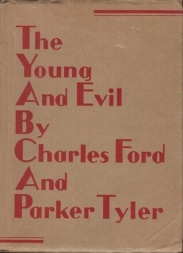

The appearance of these women–who never utter a line–reminded me of the fantastical and outlandish opening chapter of The Young and Evil, where the second line which reads:

“There before him stood a fairy prince and one of those mythological creatures known as Lesbians.”

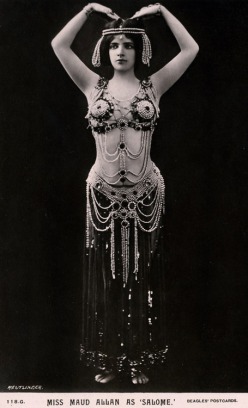

There’s lots to unpack here–which I do in my thesis!–one of which is the tongue-in-cheek presentation of lesbian women who indeed have been historically treated as “mythological creatures” (consider the widely circulated legend that lesbianism was never illegal in Britain because Queen Victoria refused to believe such a thing existed). This isn’t a far cry from how they are presented in Auntie Mame, kooky “types” just as strange and “exotic” as a brownface maharajah with a monkey perched on his shoulder, intended to make the audience pop their eyes in wonder.

And yet, problematic representation aside, I have to admit I was still glad to see them there at all.

I also later realized I hadn’t registered that the same women appear earlier in the scene, foregrounded for several seconds during Patrick’s first glimpse of the party. Only this time they are smiling and sharing a laugh with another guest–a woman who presents as more femme, but on closer inspection sports neckwear that evokes a man’s string tie.

Slowing down the pace to capture images, it also became clear a small interpersonal drama seems to take place between the three, which include a disapproving grimace and indifferent drag on a cigarette…

And for the briefest of moments, these queer ladies seem more than mere “types” and seem to possess a life of their own.

And for the briefest of moments, these queer ladies seem more than mere “types” and seem to possess a life of their own.

WORKS CITED

Auntie Mame. Dir. Morton DaCosta. By Betty Comden and Adolph Green. Perf. Rosalind Russell, Forrest Tucker, Coral Browne, Fred Clark, Roger Smith, and Peggy Cass. Warner Bros. Pictures, 1958. DVD.

Ford, Charles Henri, and Parker Tyler. The Young and Evil. 1933 New York: Masquerade, 1996. Print.

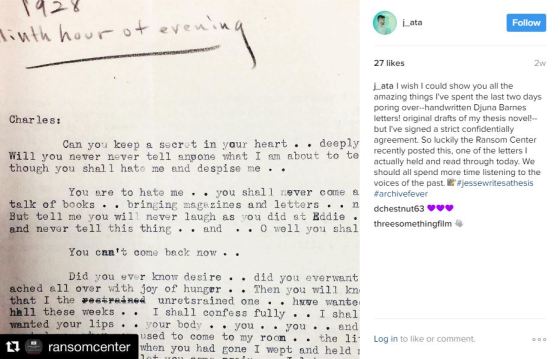

The most important development which specifically warrants an update post, however, is that after many years of hoping and scheming I was finally able to do some actual archival research for this thesis. Two weeks ago I spent three days at the University of Austin’s

The most important development which specifically warrants an update post, however, is that after many years of hoping and scheming I was finally able to do some actual archival research for this thesis. Two weeks ago I spent three days at the University of Austin’s