Tirza True Latimer’s most recent monograph is a slim yet substantial examination of a “network of enterprising outliers” that profoundly influenced art and culture making in the first half of the twentieth century, but have been generally been omitted from most accounts of modernism. But “why,” as she asks in the opening lines of the introduction, “do their names no longer strike a chord?”

Tirza True Latimer’s most recent monograph is a slim yet substantial examination of a “network of enterprising outliers” that profoundly influenced art and culture making in the first half of the twentieth century, but have been generally been omitted from most accounts of modernism. But “why,” as she asks in the opening lines of the introduction, “do their names no longer strike a chord?”

Of course, this is a question and topic familiar to anybody who has spent any amount of time reading through this blog, so it is perhaps no surprise that Eccentric Modernisms deals with exactly the same type of material featured here: the communities of transatlantic queer modernist artists that established social networks to support their artistic endeavors.

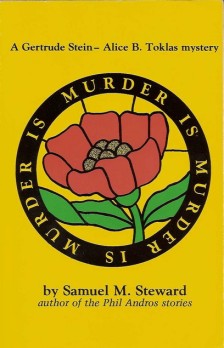

Rather than launching a project of recuperation or attempting to “fix” established historical discourses, however, Latimer simply characterizes her book as “three case studies,” devoting a chapter each to Dix Portraits, a collaborative and lavishly produced publication which featured poems by Gertrude Stein and artwork by five of her then-current protégés, the mounting of the Stein and Virgil Thomson’s opera Four Saints in Three Acts in 1934, and View Magazine, the innovative art journal edited by Charles Henri Ford and Parker Tyler during the 1940’s. The decision to direct all focus solely on three specific examples of “collectively produced art publications, performances, and ephemera” proves to be an elegant one in its dexterity and concision, with Latimer providing evocative details and minutiae to tacitly state the case for her larger arguments.

But why eccentric modernisms, as opposed to any number of other modifiers—queer, bad, pop, improper, impossible, cosmopolitan, and so many others—that been attached to modernism in recent years? Latimer admits that “the distinction between queer and eccentric may not matter,” though it serves as a useful differentiation from other synonyms, such as marginality (4). In a conversation that aired on Yale University Radio, I was interested to find out that Latimer had actually started out using “queer modernisms,” but ultimately decided that for this project “queer” wasn’t intended to be “necessarily attached to a specific notion of sexuality,” but was instead a “more capacious term.” The distinction makes sense within the context of Latimer’s overall argument, even as it also reaffirms why I continue to use “queer modernisms” in my own work (I do want to retain some kind of basis in sexual orientation and/or behavior).

But why eccentric modernisms, as opposed to any number of other modifiers—queer, bad, pop, improper, impossible, cosmopolitan, and so many others—that been attached to modernism in recent years? Latimer admits that “the distinction between queer and eccentric may not matter,” though it serves as a useful differentiation from other synonyms, such as marginality (4). In a conversation that aired on Yale University Radio, I was interested to find out that Latimer had actually started out using “queer modernisms,” but ultimately decided that for this project “queer” wasn’t intended to be “necessarily attached to a specific notion of sexuality,” but was instead a “more capacious term.” The distinction makes sense within the context of Latimer’s overall argument, even as it also reaffirms why I continue to use “queer modernisms” in my own work (I do want to retain some kind of basis in sexual orientation and/or behavior).

It was thrilling—and sometimes with a twinge of jealousy, I admit—to read through Latimer’s monograph, as she explores many of the exact same topics that I’m working through in my thesis: the difficulties of retrospectively applied terms and categories, the appeal of queer artistic networks, the motivation behind collaborative art making, the pleasures and perils of Gertrude Stein’s patronage, the nature of Charles Henri Ford and Parker Tyler’s artistic relationship, how and why so many things—even things which seem critically important—become “lost,” as well as the most effective strategies for recovering them. I suspect much that is here will find its way in one form or another in my own thesis, whether directly or conceptually. Latimer has been at the forefront of so much of the key scholarship of queer modernism (particularly her books dealing with lesbian expatriatism, the “modern woman,” and Stein’s enduring and multifaceted influence on modernism), and I suspect that Eccentric Modernisms is opening up space for a lot more work on these topics—which hopefully includes my own.

Eccentric Modernisms is available for purchase through the University of California Press.

View cover designed by Joseph Cornell, January 1943

Works Cited:

Latimer, Tirza True. Eccentric Modernisms: Making Differences in the History of American Art. Berkeley: U of California, 2016. Print.

The most important development which specifically warrants an update post, however, is that after many years of hoping and scheming I was finally able to do some actual archival research for this thesis. Two weeks ago I spent three days at the University of Austin’s

The most important development which specifically warrants an update post, however, is that after many years of hoping and scheming I was finally able to do some actual archival research for this thesis. Two weeks ago I spent three days at the University of Austin’s