From the Anthology Film Archives website, a delightful photo by photographer Katherine Bangs from a preview of the experimental film Narcissus by Willard Maas and Ben Moore in 1955.

Those pictured, from left to right, are pioneering queer filmmaker James Broughton, Julian Beck, the co-founder of The Living Theatre, painter and experimental filmmaker Marie Menken, and Tyler.

Menken and Maas were married, and their friend Andy Warhol famously called them “the last of the great Bohemians. They wrote and filmed and drank (their films called them ‘scholarly drunks’) and were involved with all the modern poets” (Nel 208). It has also been long rumored that Edward Albee based Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?‘s infamous Martha and George on the temperamental pair.

In his collection Underground Cinema, Parker writes at length about Narcissus, which he characterizes as a “Cocteau-influenced film:”

The myth of Narcissus and Echo is set forthrightly in a sort of city slum, a socially deserted warehouse district, where the hero is an infantile young homosexual living a hermit’s penurious life of wandering the streets, collecting toylike fetishes, and daydreaming… (219)

He goes on to state:

Narcissus is a serious and sensitive commentary on a deluded type of homosexual whose infantile withdrawal flows from mental and nervous instability. Without its mythological sensibility, however, the film would have achieved its poetic level” (219)

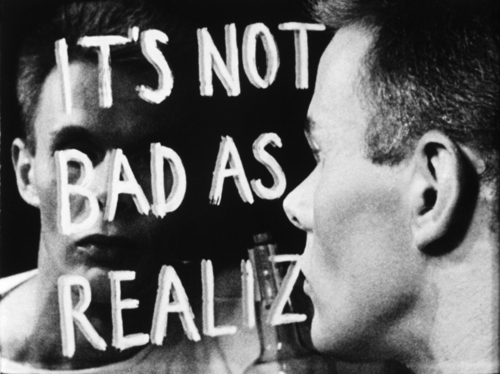

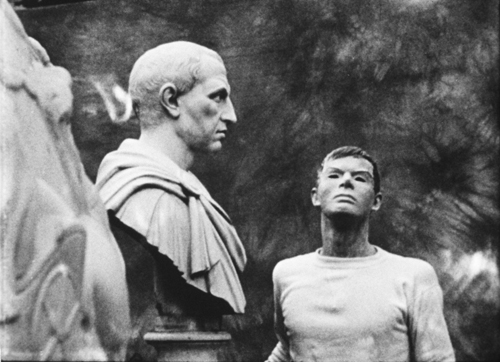

Anthology Film Archive also has a lovely gallery of stills from Narcissus, which I have long wanted to see but have yet been able. A few choice images:

Provenance

Katherine Bangs

“Portrait of James Broughton, Julian Beck, Marie Menken, and Parker Tyler, at the preview of the film Narcissus” (December 15, 1955)

Source: Anthology Film Archives

Willard Maas and Ben Moore

Stills from Narcissus (1956)

Source: Anthology Film Archives

Works Cited

Manchester, Lee. “Who’s the Source for Virginia Woolf?” Wagner Magazine, 2013.

Nel, Philip. Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss: How an Unlikely Couple Found Love, Dodged the FBI, and Transformed Children’s Literature. University Press of Mississippi, 2012.

Tyler, Parker. “History and Manifesto.” Underground Film: a Critical History, Da Capo Press, 1995, pp. 197–220.

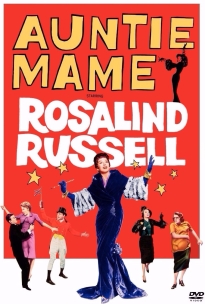

Sometimes a detail that appears in the frame of a film instantly seizes our attention and momentarily crowds everything else out–a situation I encountered during a recent rewatch of the 1958 film adaptation of

Sometimes a detail that appears in the frame of a film instantly seizes our attention and momentarily crowds everything else out–a situation I encountered during a recent rewatch of the 1958 film adaptation of

And for the briefest of moments, these queer ladies seem more than mere “types” and seem to possess a life of their own.

And for the briefest of moments, these queer ladies seem more than mere “types” and seem to possess a life of their own.