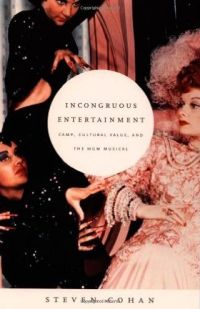

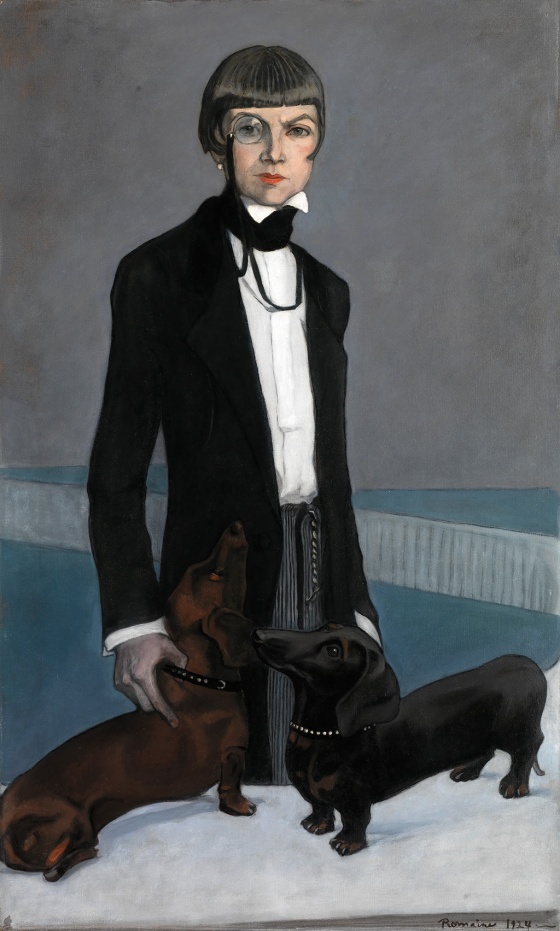

Dolly Wilde (Slaveya Minkova) and Djuna Barnes (Josefin Granqvist) appearing in a cinematic reimagining of the “Ladies Almanack” by Djuna Barnes

Shame on me for failing to make some kind of mention of Djuna Barnes’s birthday last Friday (June 12), but considering that the date of her passing is June 18, I figure it would be appropriate over the next several days to celebrate all things DB.

For my first post, I thought I’d bring some attention to a fascinating project I’ve been following for a while now, a film adaptation of Barnes’s fascinating/bewildering/bewitching roman à clef Ladies Almanack which is currently in production. It is being written and directed by Chicago-based writer, performer, and filmmaker Daviel Shy.

Cover of “Ladies Almanack” with illustration by Djuna Barnes

According to the film’s website, The Ladies Almanack will be “a feature-length experimental narrative film,” and that it will be “a kaleidoscopic tribute to women’s writing through the friendships, jealousies, flirtations and publishing woes of authors and artists in 1920’s Paris.” For those not familiar with Barnes’s original text, it was written in 1928 and privately published that same year, and reportedly undertaken for the amusement of Natalie Clifford Barney and the circle of lesbian artists associated with the celebrated salon she hosted in Paris. Drawing equally upon literary elements both archaic and modernist, in mock-Rabelaisian style Barnes casts Barney and her friends (which include Romaine Brooks, Radclyffe Hall, Mina Loy, Janet Flanner, and many others) and almost beatifies them, casting the coterie’s various in-jokes, tangled relationships, and interpersonal tensions almost as a form of medieval hagiography. I haven’t at all managed to do justice to Ladies Almanack in this brief description, but will just say that while I found this a strange and perplexing work on my first reading, after some research and several more reads I now find it to be as screamingly funny as much as it is artistically and conceptually innovative. Barnes’s witty and characteristically eccentric illustrations only further emphasize these qualities.

Mimi Francetti (Fannie Sosa) and Lily de Gramont (Merci Michel) in “The Ladies Almanack”

I’m pexcited about Shy’s adaptation precisely because all available information and imagery makes it seem like there is little interest in “faithfully” adapting Barnes’s anarchic text, but rather Shy is extensively–and I’d say appropriately–reimagining the project Barnes herself originally set out to undertake. According to the film’s website, “each character is a hybrid of the historically researched figure and the contemporary artist who portrays her,” and, intriguingly, Shy is casting Hélène Cixous, Luce Irigaray, and Monique Wittig as narrators, with Cixous actually portraying herself and Eileen Myles embodying Wittig. Iconic queer filmmaker and actress Guinevere Turner (Go Fish, The L Word) will play Liane de Pougy. My impulse is that Shy is undertaking some really clever strategies to access this text within the context of 2015, with the potential for representing how the queer legacies of this particular storied moment of the queer past possesses a legacy that continues to resonant in the queer present.

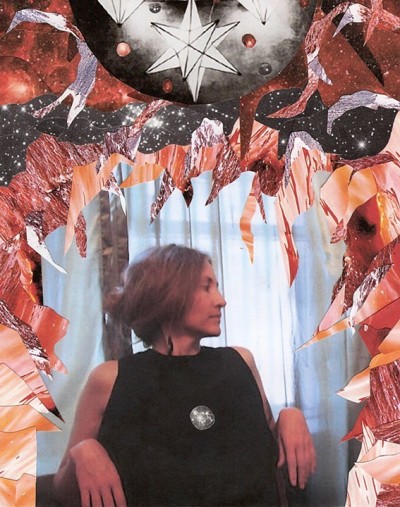

Collage Cover of “The Ladies Almanack” by Sarah Patten

I’m also particularly pleased that the film is intentionally taking on an experimental style, and the images that have been shared on the film’s website and through other social media sources have brought to mind the work of numerous queer artists, from the lush style and evocative anachronism of Derek Jarman and Werner Schroeter, to Barbara Hammer’s erotic utopianism, to the stylized posing of Claude Cahun’s portraiture, to the inventive and insatiable cultural bricolage of Jack Smith. The film’s stated “Bibliography” demonstrates that Shy & co. have definitely done their homework in regards to literary based research, and I’m expecting the same regarding the film’s visual sensibility, which certainly seems to be operating within the tradition of queer non-mainstream filmmaking.

The film’s Profile page also excites me, as it is clear that the Ladies Almanack will be representing a large swath of the contemporary queer community in all of its diversity, beautiful idiosyncrasy, and immense creative energy.

The production is still raising funds to help get the project completed–I donated last week during a fundraiser they were holding. Otherwise, keep up the project through the website’s news page, its Facebook page, or tumblr site. I’ve also been enjoying wandering through Daviel Shy’s personal site.

To close, several more collages by Sarah Patten, which are reportedly going to serve as chapter headings in the film. To say I’m obsessed with them is an understatement.

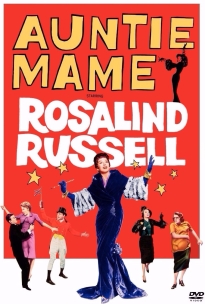

Sometimes a detail that appears in the frame of a film instantly seizes our attention and momentarily crowds everything else out–a situation I encountered during a recent rewatch of the 1958 film adaptation of

Sometimes a detail that appears in the frame of a film instantly seizes our attention and momentarily crowds everything else out–a situation I encountered during a recent rewatch of the 1958 film adaptation of