In my recent post spotlighting the several lesbian party guests glimpsed in the background of Auntie Mame I mention how for several seconds a tiny little interpersonal drama seems to play out, conveyed through gesture and expression. What I didn’t note was how these women actually brought to mind two specific historical figures: longtime partners Radclyffe Hall and Una Vincenzo, Lady Troubridge, perhaps the most well known lesbian couple of the early twentieth century. During the last years of the 1920’s, the exact period in which this scene in Auntie Mame takes place, Hall was at the height of her public notoriety due to public outcry against her novel The Well of Loneliness, culminating in an obscenity trial in British courts in late 1928. It’s kind of fun to think of her and Una dropping by one of Mame Dennis’s extravagant evening soirées, an unexpected convergence of queer modernist and mainstream Hollywood aesthetics.

Here is the first glimpse of the women in the tumult of the party:

as well as a closer look:

Here is Troubridge and Hall in 1933:

In the photo above Hall isn’t wearing her signature hat and it is impossible to make out the details of her jacket and other garments, but there are undeniable similarities between Hall’s distinctive facial features and the woman on the far left, and the hairstyle of the woman on right very much resembles Troubridge’s silver coiffure of this period.

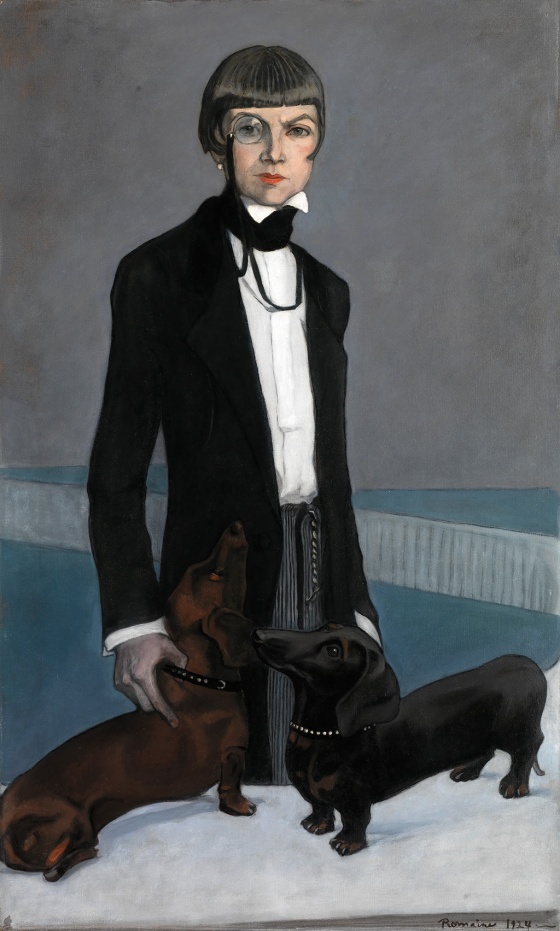

Throughout her adult life Hall almost exclusively wore masculine suits, while Troubridge alternated between masculine and more conventionally feminine clothing. Which is interesting, considering the most well-known image of Troubridge is the striking portrait Romaine Brooks painted in 1924 where she appears as a lesbian dandy with a severe bobbed haircut:

Brooks’s portrait has since become an essential image of pre-Stonewall lesbian iconography.

Nearly as well known is this handsome 1928 portrait of Hall in profile:

So did the filmmakers of Auntie Mame, portraying a wild bohemian party from the late 1920’s, intentionally make a sly reference to the period’s most famous lesbian couple? Impossible to say, of course, though it should be noted that it was something of an open secret in Hollywood that Auntie Mame‘s costume designer, the prolific Orry-Kelly, was a gay man, and he would almost certainly have been aware of Hall, and likely Troubridge as well. And it’s not at all a stretch to imagine that as both international celebrities and artistic figures, Hall and Troubridge would have found the oversized doors of Mame Dennis’s penthouse thrown wide open to them, their hostess delighted to have them join her assembly of “eccentrics.”

But whether or not these visual resemblances between these extras and Hall and Troubridge was a deliberate choice is, in the end, somewhat beside the point. By the 1950’s, when Auntie Mame was made, the figures of Hall and Troubridge were so firmly established in the public imagination as archetypes of lesbian identity and sapphic sartorial style that American film audiences would directly link them back to The Well of Loneliness and its famous author anyway–so why not extend them a cinematic invitation to the party?

PROVENANCE:

(Top to Bottom)

Auntie Mame. Dir. Morton DaCosta. By Betty Comden and Adolph Green. Perf. Rosalind Russell, Forrest Tucker, Coral Browne, Fred Clark, Roger Smith, and Peggy Cass. Warner Bros. Pictures, 1958. DVD.

Troubridge and Hall attending first night of When Ladies Meet (1933)

Credit: Sasha / Stringer

Getty Images

Una, Lady Troubridge (1924)

Romaine Brooks

Oil on canvas

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Radclyffe Hall (1928)

Credit: Russell / Stringer

Getty Images

Sometimes a detail that appears in the frame of a film instantly seizes our attention and momentarily crowds everything else out–a situation I encountered during a recent rewatch of the 1958 film adaptation of

Sometimes a detail that appears in the frame of a film instantly seizes our attention and momentarily crowds everything else out–a situation I encountered during a recent rewatch of the 1958 film adaptation of